When considering our present immigration policies, it is useful to examine the history of Italian immigration in this country.

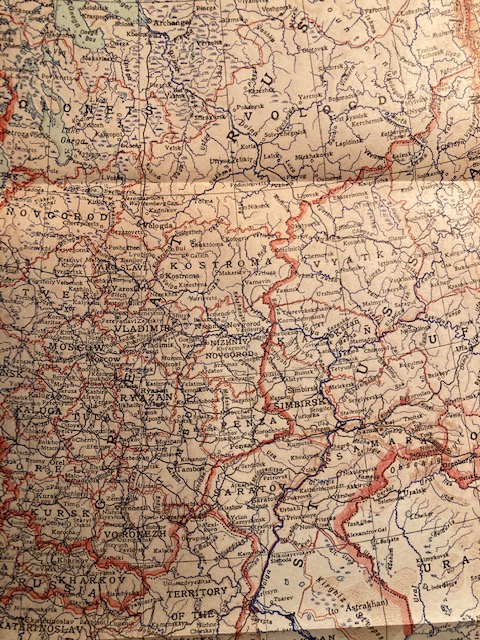

Immigration from Italy to the United States soared at the beginning of the twentieth century. From 1900 to 1905, the numbers increased from 171,735 to 479,349. Between 1880 and 1921, 4.2 million Italians, most from southern Italy, entered the country. Many Americans thought this flood of immigrants was harmful. The 1911 Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Brittanica entry on immigration, seemingly referring to all those Neapolitans, Calabrians, and Sicilians, put it delicately: “The influx of millions of persons of different nationalities, often of a foreign language and generally of the lower classes, would seem to be a danger to the homogeneity of a community. The United States, for instance, has felt some inconvenience from constant addition of foreigners to its electorate and population.” Though citing no reference, the essay goes on, “The foreign-born are more numerously represented among the criminal, defective and dependent classes than their numerical strength would justify. They also tend to segregate more or less, especially in large cities.”

Almost none of the Italian immigrants — largely illiterate rural peasants who professed a religion that was still not considered acceptable by many Americans — spoke English. Many made little effort to learn it. These Italian immigrants, 75% of whom were male, did not plan to become Americans. As the Britannica put it: “It is notorious that the Italians who emigrate to the United States largely return.” Aristide Zolberg reports that while roughly 35% of all immigrants to the United States from1908-1923 returned to their homelands, more than 50% of Italians did. Other estimates of returnees are as high as 78%. (These “birds of passage”—young Italian men who migrated alone, earned money, and returned to Italy—have regularly popped up in histories, novels, and memoirs. For example, a character in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is a man born in Italy who had been a cabdriver in Chicago and, after saving money, moved back to Italy. Daphne Phelps in her charming A House in Sicily refers to “a diminutive Sicilian barber who had spent nine years in New York before returning with his savings.”)

Thus, the arriving Italians did not appear to contribute much to the American economy. After all, they were destitute upon entry. A 1902 report said arrivals at Ellis Island from southern Italy came with the least amount of savings of any immigrant group, $8.67. They worked and saved, but not to invest or spend it in America. They sent or took their savings back to Italy.

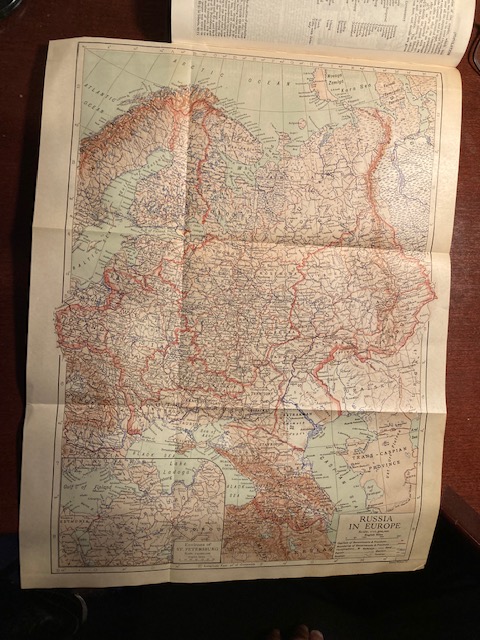

In addition, many Americans believed about southern Italy what the Encyclopedia Brittanica said: “Countries sometimes aid or assist immigration, including the assisted emigration of paupers, criminals or persons in the effort to get rid of undesirable members of the community.” (That Eleventh Edition also contains this rather discomfiting statement: “Finally, we have the expulsion of Jews from Russia as an example of the effort of a community to get rid of an element which has made itself obnoxious to the local sentiment.”)

Certainly, the Italian arrivals seemed dangerous. Michael Dash reports in The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia, “Nineteen Italians in every twenty of those passing through Ellis Island were found to be carrying weapons, either knives or revolvers, and there was nothing in American law to stop them from taking this arsenal into the city. The Sicilian police were said to be issuing passports to known murderers to get them out of the country.”

Even if the issuing of such passports was untrue (Dash does make clear that the many of the founders of the American mafia fled Sicily after convictions or charges for murder and other crimes), the American populace was led to believe that Italian criminality was rampant in the U.S. The sensational American press of the time played up murders and other crimes committed by Italians in New York and New Orleans and focused on the killing in Sicily of New York police lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, who was seeking Italian criminal records of Italians living in the United States. Not surprisingly, the 1903 New York Herald gave this warning: “The boot [of Italy] unloads its criminals upon the United States. Statistics prove that the scum of southern Europe is dumped at the nation’s door in rapacious, conscienceless, lawbreaking hordes.”

Many American citizens believed that Italian immigrants should never be naturalized. This led to the question, “Are Italians white?”, an issue discussed in many places including by Isabel Wilkerson in Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent (2020), and by Paul Morland in The Human Tide: How Population Shaped the Modern World (2019). One of my favorite meditations on the topic is in the must-see movie Sorry to Bother You. The film’s characters are discussing how blacks make pasta differently from whites and how it should be made. In an attempt to end the discussion, the protagonist states that spaghetti is Italian. Another character incredulously asks, “Italians are white?” “Yes.” “For how long?” The protagonist replies, “For about sixty years.”

The whiteness of Italians was an issue because of our naturalization law, which in 1790 allowed only free white persons to become citizens. This was slightly modified in 1870 to allow the naturalization of former enslaved people, but otherwise a person in the early twentieth had to be white to become a naturalized citizen. (“White” was not defined, and this restriction led to some bizarre court cases. In 1923 the Supreme Court ruled that a high caste Sikh, who pointed out that his ethnicity was Aryan and who had fought for the United States in World War I, was neither white nor black and could not be naturalized. A Court of Appeals case in 1915, however, ruled that a Syrian could become an American citizen.)

Instead of grappling with the issue of Italian whiteness, Congress, concerned about the Italian influx and the immigration from eastern Europe, changed the law to make it harder to immigrate to the U.S. from “undesirable” places. After this 1924 act, Italian immigration dropped from 283,000 in 1914 to 15,000.

And the moral? The Italian immigrants, seen by many as lawless, destitute, illiterate thugs who could not speak English and did not try to learn it, who were a danger to the American fabric and a drain on the economy, and who smelled bad because they ate — God help us! — garlic, are now as American as an American can be. When we discuss immigration today, we should remember this history. As the Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannic said about the difficulties for the host country from immigration, “Nevertheless, the process of assimilation goes on with great rapidity.”