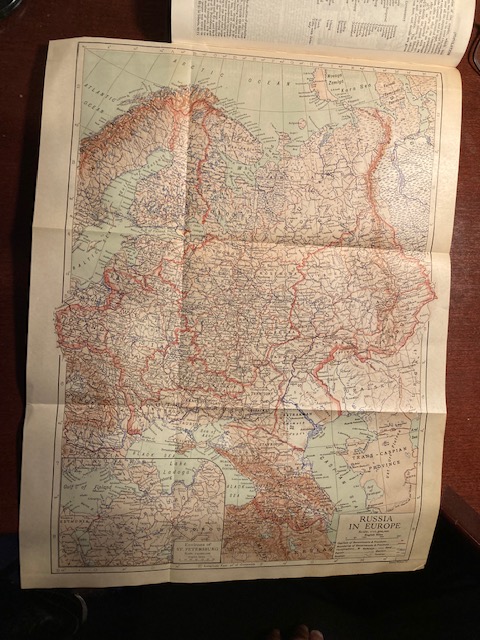

Putin, coming out of relative obscurity, was elected Russian president in 2000 with 53% of the vote. He consolidated his power quickly and extensively in ways large and small and was reelected in 2004 with a reported 71% of the vote. The Russian constitution then only allowed the president two consecutive four-year terms preventing his run for a third term. Putin endorsed Dmitry Medvedev for the March 2008 election and Medvedev got more than 70% of the votes. He then appointed Putin his prime minister.

A constitutional change during Medvedev’s term increased the presidential term to six years, and Putin again ran for president in 2012. The election was viewed by many within and without Russia as corrupt. In her book The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (2012), Masha Gessen reports: “Putin declared victory in the first round of the presidential election, with 63 percent of the vote. Holding a virtual monopoly on the ballot, the media, and the polls themselves, he could have claimed any figure, but he opted for a landslide, and a slap in the face to the Movement for Fair Elections.” The Movement had been part of widespread demonstrations that started months before the election. The protestors wore white ribbons, which Putin crudely sexualized by saying the cloth looked like condoms.

Putin won, but it was clear that a significant portion of Russians were unhappy with him and the direction of their society. Putin had invaded Georgia in 2008, which perhaps was initially popular, but became less so as the war wore on. Privatization of industry had put money into private hands, but little of it went to anyone other than what are now known as the oligarchs. Russians could increasingly see the results of wealth, but few experienced it. Russia became the most economically unequal society in the world. More and more people felt dangerously unsettled. Gessen again: “Many Russians, however, got poorer—or at least felt a lot poorer: there were so many more goods in the stores now but they could afford so little. Nearly everyone lost the one thing that had been in abundant supply during the Era of Stagnation: the unshakeable belief that tomorrow will not be different from today. Uncertainty made people feel ever poorer.” And people took to the streets in numbers that Putin could not ignore.

He responded not by trying to distribute wealth more equally, increasing civil liberties, or having fairer elections. Instead, in something that should feel familiar to Americans today, he sought to unite Russians by launching an anti-homosexual crusade. Gessen states, “In the spring of 2012, Putin decided to pick on the gays. In the lead-up to the March 2012 election, faced with mass protests, Putin briefly panicked. . . . And faced with the protest movement, the new Kremlin crew reached for the bluntest instrument it could: it called the protesters queer.” Timothy Snyder in The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America sees Putin as making this an external threat: “Some intractable foreign foe had to be linked to protestors, so that they, rather than Putin himself, could be portrayed as the danger to Russian statehood. Protestors’ actions had to be uncoupled from the very real domestic problem that Putin had created and associated with a fake foreign threat to Russian sovereignty. [The protestors] were mindless agents of global sexual decadence whose actions threatened the innocent national organism.” Putin claimed that these protestors were the tools of a foreign power, a power embodied in the person many American conservatives loathed. “Three days after the protests began, Putin blamed Hillary Clinton for initiating them: ‘she gave the signal.’” A few days later, without providing evidence, he claimed that the protestors had been paid.

The propaganda maintained that the forces promoting sodomy were not just trying to affect Russia. They were also infiltrating Ukraine. “European integration (of Ukraine) was interpreted by Russian politicians to mean the legalization of same-sex partnership (which was not an element of Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU) and thus the spread of homosexuality.” Gessen tells us that a Russian politician “warned that if Ukraine went west, that would lead to ‘a broadening of the sphere of gay culture, which has become the European Union’s official policy.’ Over the next couple of months, the image of the Western threat menacing Ukraine broadened to include not only the gays but also the Americans, for whom the gays were always a stand-in anyway.”

Whether or not American manifest destiny compares to Russian exceptionalism, Putin’s turn to sexual matters does have American parallels. How American does this sound? Putin announced, Gessen reports, that he was “defending traditional values.” Russia passed legislation “not only banning ‘homosexual propaganda’ but also ‘protecting children from harmful information,’ which meant, first and foremost, any mention of homosexuality, but also mention of death, violence, suicide, domestic abuse, unhappiness, and, really, life itself.” (The law was entitled, “For the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating for a Denial of Traditional Family Values.” Perhaps it produces a snappy acronym in Russian.) Russian kiddies should not learn of things that might make them uncomfortable. It is clear that a similar agenda is being implemented in an increasing number of American schools.

Putin has learned a basic political trick: when the topic is about the shortcomings of Russia or of Putin himself, shift the topic. “Putin was enunciating a basic principle of his Eurasian civilization: when the subject is inequality, change it to sexuality.” American conservatives have followed a similar path to avoid confronting American shortcomings. Instead of addressing homelessness, switch the topic to any number of other topics — critical race theory, Black Lives Matter, DEI, or the ever-handy rainbow flag of gaydom and transgenderism. American conservatives and Putin share the goal of wanting to make “politics about being rather than doing.”

Russia has recently been meddling in the affairs of other countries. For example, when Germany’s Angela Merkel admitted Syrian refugees causing a backlash among some of her constituents, Russia increased its bombing of Syrian targets, thereby creating more refugees. Through Twitter accounts and the media outlets it controls, Russia published false reports about the crime wave in Germany supposedly caused by the refugees. This had me thinking about conservatives who talk about crimes and diseases brought by immigrants to this country. They have little data to back up their claims and seldom mention that almost all who come here expect to work hard to attain a better life. Moreover, they fail to mention that birth rates are dropping in the U.S., and we need those workers.

Before the vote on Scottish independence, Russian media, hoping to encourage the disruption of the United Kingdom, rattled on about the terrible consequences for Scotland if it remained in Great Britain. After the referendum failed, Russia cast doubt about the vote’s validity. Internet video suggested vote rigging, and the videos were promoted on Twitter by accounts based in Russia. Timothy Snyder states, “Although no actual irregularities were reported, roughly a third of Scottish voters gained the impression that something fraudulent had taken place.” Sound familiar?

Russia favored Brexit–anything to disrupt European unity–and over 400 Twitter accounts heavily promoting the “exit” position were traced to Russia. Russian media did not attack the outcome of the referendum. Snyder says, “This time, no Russian voice questioned the result, presumably since the voting had gone the way Moscow had wished. Brexit was a major triumph for Russian foreign policy to weaken the United Kingdom. The margin of the vote was 52% for leaving and 48% for staying.”

Why should Russia seek to destabilize other countries? There are at least two reasons. Masha Gessen reports that Putin understands strength to mean that “the country is as great as the fear it inspires.” Thus, Russia’s ability to influence the internal affairs of other countries demonstrates its powers. In addition, because Russia has not been able to raise itself up in the world, it has begun to define success “not in terms of prosperity and freedom but in terms of sexuality and culture, and [suggests] that the European Union (and the United States) be defined as threats not because of anything they did but because of the values they supposedly represented.” Russia’s method of moving up in the standings is to tear others down. Snyder points out, “The essence of Russia’s foreign policy is strategic relativism: Russia cannot become stronger, so it must make others weaker. The simplest way is to make them like Russia.”

The reasoning would suggest that Russia thinks itself better or, at least, not so bad when people in other countries doubt their institutions and their society’s values. Russia suggested that a Conservative win in the UK was the result of a rigged election. If it can get Britishers to believe that, Russia’s elections appear similar to British ones. Moscow does not try “to project some ideal of their own, only to bring out the worst in the United States.” Under communism, the Soviet Union tried to convince the world that it had a better system than the west — one that would eventually prevail and bring a better life for the Soviets and people around the world. Russia no longer has that ideology. It cannot produce or promise an improving society; it can only tear down others.

It is more than a little frightening to picture Putin giggling in triumph, but he must be more than a little pleased with recent American trends as conservatives seek to undermine the basic validity of our elections. If, in this bastion of democracy, our votes are rigged, then Russian elections look better. The Russian portrayal of America as a land of sexual decadence is only promoted when conservatives “find” homosexual and transexual groomers hiding in American classrooms. Russia’s own repression of Russians who contest their country’s direction looks sounder when U.S. schools are portrayed as places for racial and woke indoctrination. The conservatives may not be consciously seeking to make Putin stronger, but they are unwittingly playing into his hands. Perhaps when the cameras are off, he runs victory laps around those huge conference tables he often sits behind wearing a MAGA cap. And giggling.